July 30, 2017 / Zoenie Liwen Deng

Participatory art on-off a digital platform—a Mobius Strip — On Cyber Nails in Curated Nails

| Principal investigator: | Zoénie Liwen Deng |

| Institution: | ASCA, University of Amsterdam |

Abstract:

How does participatory art in China make use of digital platforms? What kind of relationships are triggered and enabled by the digital and digitalisation in participatory art projects? This field note, through analysing Cyber Nails (2014), a subproject of the participatory art project Curated Nails (2014–2016), explores the chiasm, the Mobius-strip-like relationship between online and offline, between showing and seeing. This means that participants in the project enter into the uncanny mirrored relationship between the corporeal self and the digital self/other, and are involved in the cycle of desire for seeing and being seen.

Key terms:

participatory art, digital, corporeal, chiasm, exhibitionism, voyeurism

If you meet a Chinese person who has a smart phone, and want to connect with them, they will probably ask: ‘Will you scan me or will I scan you?’ This does not literally mean that they are going to scan you, it just means that either they will scan your WeChat QR code, or the other way round. WeChat has become a popular social media application for Chinese people of different age groups: 697 million people are currently making use of this app (Qianzhanwang, 2016). WeChat is similar to Whatsapp, but has many extra functions, e.g. people can post things in ‘moments’, which is more like Facebook, and the official accounts of organisations can post articles regularly on their platforms, which can be shared by WeChat users. Every user can generate content on this platform, and自媒体 (‘zi meti’,‘self-mediatise’ ), a term used by Chinese columnists, critics, and intellectuals to describe the situation in which the digital and the internet enable people to mediatise themselves and publicise their viewpoints, activities, images, videos and so on; everyone is able to attract attention on social media using self-mediatisation.

Likewise, in contemporary China, curators and artists mobilise their projects on digital platforms, mainly using WeChat. In my PhD research project on contemporary art in China, digitisation plays an important role in promoting and calling for participation in art projects on digital platforms, in digital archivisation of artworks and art projects, and also of artworks that are created or take place in digital spaces and only exist digitally. My research encompasses projects such as the socially engaged art project 5+1=6, and Curated Nails, both of which utilise the digital social media platform WeChat for publicisation and mobilisation of their projects, and also for archivisation.5+1=6 was launched on WeChat by the Second Floor Publishing Institute in Beijing, together with artist and art professor Li Yifan, in September 2014. In their open call for participation, the initiators invited cultural practitioners to ‘choose one of the villages/towns between the fifth ring road and sixth ring road to conduct an investigative project in an artistic way’ (Second Floor Publishing Institute, 2014). Some subprojects of 5+1=6 also used social media to conduct their research on inhabitants in their chosen villages, but the mediality of the digital platform was treated as an enabler and a means of producing offline results for the projects. In this field note, however, I would like to elaborate on a project that imbricates online offline participation in various ways besides mobilisation, and manifests the interfaciality between the digital and the physical, social media and ‘meatia’—meat-media (a composite word used by artists in China to describe the use of the human body in art works and practices.).

In the same year as 5+1=6, in September, another art project was also launched on WeChat: Curated Nail, by Ye Funa. Ye invited ‘curators to manifest exhibition themes and concepts on the tiny space of human nails, breaking the barriers of ‘daily display’ and ‘art exhibition’’ (Ye, 2015). It started as an open call for participation on WeChat where everyone could be a curator, regardless of his or her profession. On the one hand, this project used a part of the human body as an unconventional space for an art exhibition (although it is very common in performance art for the human body to generate a performance, which renders the body as the site of gaze and affect; in cyborg art, the body itself is the site of experiment and exhibition). On the other hand, it mimicked and parodied the institutional exhibition system/white cube model on the fingernails. It also had a kinship with manicure, which has been popular for the last two decades in China. Nail salons can be found in shopping malls and on the streets; articles on this year’s trendy nails appear on websites; the ever-changing colourful products appear on the shelves of nail polish in shops. The project’s affinity with manicure made it more accessible and amiable to people who were not in the art world, or were less ‘serious’ in the art world. Ye initially wanted to conduct this project in a formal way, but no art institute was willing to host the project (Ye, 2016), which was one of the main reasons why she initiated the project online.

From its inauguration until November 2016, more than 100 subproject proposals were received. Some were realised offline, some were executed online, most of the time via WeChat, some took place both on- and offline, mirroring one another, and the rest remained as proposals in the digital space. The choice of execution online or/and offline for each subproject in Curated Nails depended on its curator. Ye herself also curated some shows and activities on and around fingernails. In this field note, I will analyse one subproject that was proposed and executed by Imo, a self-proclaimed ‘net artist’. This was a ‘net art’ project in which the human body was nonetheless involved and was situated in-between, inside and outside the digital world and the physical world. Digital art is art that uses the inherent possibilities of the digital, and is produced, stored, and presented in digital format (Paul, 2008: 3). Internet art is a form of digital art that is made on and for the internet, also known as net art (Tate, 2016). In December 2014, on WeChat, Imo launched the ‘net art’ project, ‘Cyber Nail’, in which a ‘human flesh nail machine’ would paint the photographed nails of a participant, using an application, once a photo of a hand (with nails) was received. One could thus have manicure in the virtual world (Imo, 2014).

Although the nails in the digital world were painted digitally, human bodies were present and involved. Curator Karen Archey analyses how the body, in some digital artworks, is mediated by both virtual and physical space, and she tries, through her analysis, to contribute to the artistic discourse by elaborating on identity, body and sexuality (2015: 451). However, not all the cases that she chose used the human body as the space of both acting and exhibiting. In this project, if you wished to participate, you needed to first take a photo of your hand using your smart phone, during which you would use your finger to press the ‘shutter’ on your screen to capture the image of your other fingers. Then you would send your photo to Imo, and she would use her fingers to paint your digital nails. The interfaciality of this project is not only about the functionality of the interface of the application, but also the imbrication of the human body and the digital. Even though, as Jason Farman observes, the designers try to render invisible the computation and technologies of the digital system, to provide an ‘interfaceless interface’ (2012: 7), the interface between the digital world in your smart phone and your body is the screen, a physical object on which your fingers move around under your eyes.

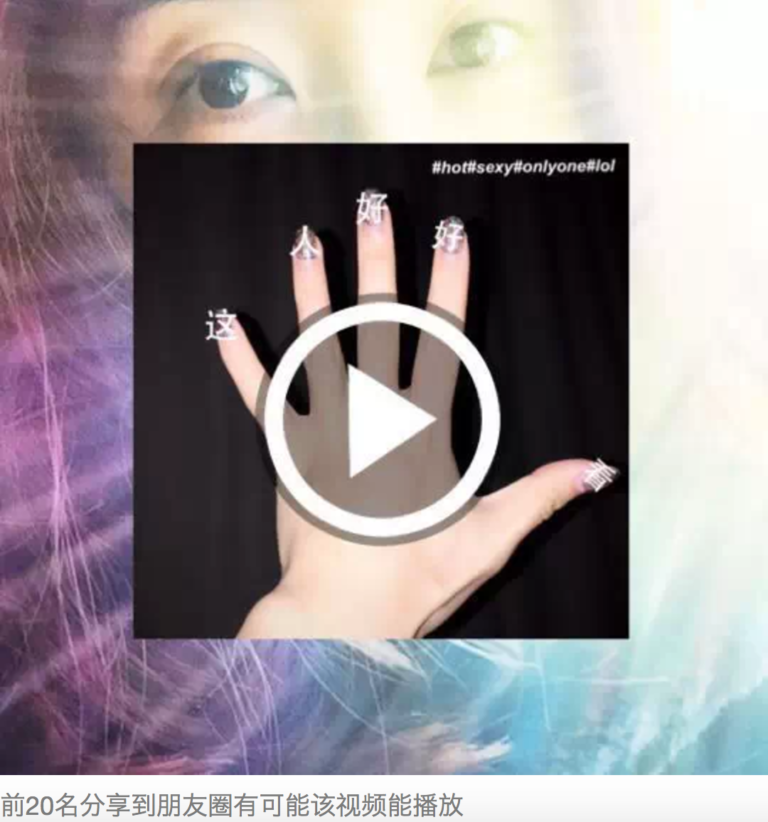

Screenshot of the post of Cyber Nail project on Exhibitionist’s WeChat account. The Chinese characters on the nails mean ‘this person is very good looking’. The sentence below says ‘the first 20 people who share this post in their WeChat moment might be able to play this video’.

Courtesy of Imo. 2014.

In the case of Cyber Nail, when Imo painted your nails, her fingers doodled and moved on your ‘fingers’, your ‘digital nails’; the size and shape of the brushstrokes on your ‘nails’ depended on the touch and movement of the fingertips of Imo. In figure 1, the woman in the background, with only the area around her eyes visible, is looking at those who are touching this image with their fingers and staring at it on their smart phones. In the top right corner is a series of hashtags (#hot#sexy#onlyone#lol) enticing people to touch the ‘play’ button with their fingers, that is on the back of a hand bearing words on the nails saying ‘this person is very good looking’. This plays with the voyeurism that is prevalent in internet culture in China: the popularity of live streaming直播—(‘zhi bo’) —is a good example. This is also a return of the performative gaze that solicits touching and seeing. At the same time, the nails above the screen and those under the screen are ‘touching’ each other in an uncanny and chiasmatic way. Your fingers never touch those in the image physically, but rather, digitally; however, in order to do so, you have to use your fingers physically. ‘Between my body looked at and my body looking, my body touched and my body touching, there is overlapping or encroachment, so that we may say that the things pass into us, as well as we into the things’ (Merleau-Ponty, 1969: 123). Your fingers are looked at by both yourself and the eyes in the digital image; your fingers are touching both the screen and the digital photo of your fingers; your fingers are touched by the screen physically and by those fingers in the image digitally. If the hand in the image is your own hand, you enter into a situation in which you digitally touch your hand that has been touched and manicured by Imo digitally. The text ‘The first 20 people who share this post in their WeChat moment might be able to play this video’ underneath this image/video seduces you to enter a circus of collective peeping in darkness—no one knows who can watch it or who is watching it, except perhaps Imo herself. If that is your hand, you are in/voluntarily involved in this Mobius-strip-like cycle of exhibitionist and voyeurist, looking and being looked at, and touching and being touched. All the cyber nails are stored in the cloud—on the WeChat account and website of Curated Nails. If you have participated in Imo’s Cyber Nail, your ‘nails’ can be summoned for display with the touch of a finger on the screen of a smart phone, digitally embodying you.

One of the cyber nail paintings. Courtesy of Imo. 2014.

To sum up, the digital here is not external or detached from the body, the flesh, and the physical. Instead, a fingernail, as a space for participation and exhibition, is both digital and bodily in an intertwined way. The digital embodies the corporeal and vice versa, blurring the binary of the corporeal self and the digital other as Moore observes (2015: 27). Participatory digital art projects like Cyber Nails do not simply create an extended and expanded space for the offline online, or replicate the physical in the digital, but enable the two-way uncanny reflection and refraction of the actual and the virtual. Cyber Nails also echoes other Chinese contemporary art projects that use live streaming to tap into the desires for showing (exhibitionism) and watching (voyeurism) of netizens, and to explore the possibilities of exhibiting contemporary art in digital space. In response to one of Imo’s nail painting (see Figure 2), I can’t believe that the digital world is only approximately 60 years old!

- ‘The white cube has various roots which all finally come together in the 1930s in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Before and after the First World War, there was a desire to show pieces of art against a background with the greatest possible contrast to the dominating colours of the paintings’. (Charlotte Klonk, in The white cube and beyond by Niklas Maak, Charlotte Klonk and Thomas Demand. Read on Tate.org.uk. 1 January 2011)