August 8, 2018 / Laura Vermeeren

Zeng Xiang – (not) being ugly

Zeng Xiang – (not) being ugly

They despise tradition, despise classics, and despise authority (Wang 2004, 14).

I belong to the traditionalists, those who study the calligraphic line. They (Xu Bing and Wang Dongling – red.) do too, but they became contemporary artists earlier on. It is like the rabbit and tortoise race; do you know that story? We are slow, but Xu Bing and Wang Dongling are fast like rabbits. I am the tortoise. [1]

Zeng Xiang’s (b. 1958) exhibition at the Art District 798 in Beijing in April 2018, where he showcased his large and highly expressive works, together with a video of himself in which he is making these artworks – moving his entire body ferociously while screaming and splashing around ink on a paper on the floor– caused quite a stir.[2] Zeng Xiang is not well known in the West, but in China’s calligraphy scenes, Zeng is often mentioned as one of the heads of a contemporary calligraphy style called “ ugly calligraphy” (丑书), although he himself does not align to that label [3] “Ugly calligraphy” came to the fore in the 1980’s and has proved difficult to pigeonhole: there is no common agreement of what constitutes this type of calligraphy (Liu 2016). Liu Zongchao traces back the phenomenon as early as the Dunhuang scriptures, arguing rightly that clumsy, ugly or childlike character-writing has always existed. The calligraphy that was specifically created for exhibition – a practice that started since the Reform and Opening up policy – accelerated, and consequently the calligraphy, Liu argues, had to be more innovative and different. He argues that “ ugly” should not be seen as an aesthetic category, but defines all those calligraphies that are disharmonious, asymmetric, and inconsistent in appearance. Among them “some are “beautiful in their ugliness”, while others are truly “ugly” (non-art).” (Liu 2016, 139)

Many opinions circulate on the phenomenon of “ugly calligraphy”, from the absolute offensive, like Wei Wei when he argues that “ ugly calligraphy” is like “ a plague”, is “incomprehensible gibberish”, spreading like germs and “polluting the younger generations” and those doing it are in “an abnormal state of mind, have a distorted soul, coupled with ignorance and shallowness”. (Wei 2014, 344) to the more mellow:

We welcome innovation. Innovation is the only way forward for the arts. To be able to innovate better, we must boldly and confidently fight against “ ugly calligraphy”. If we can not distinguish the five beauty’s, can not discern fragrance from stench and if our reasoning is unclear then we are not able to have meaningful innovation. It is like poet Ai Qing said: “ Art must have originality, but is it definitely not the case that all innovation is art. The madman is the most innovative, but he is definitely not an artist. (Wang 2004, 14)

The emotional responses within the field urge us to ask what exactly is articulated in the work of a calligrapher that is pigeonholed as making “ ugly calligraphy”, but still operates within the paradigm of calligraphy. What tactics are employed in Zeng Xiang’s work and how might we understand these? Is it possible to read these politics of aesthetics as resistance? Is the ugly a critique of the beautiful? Is it a postmodern “ anything goes” attempt? Or are a Rancierian politics underlying these works – is Zeng Xiang redistributing the existing sensible by reimagining a calligraphy that is not beautiful, not symmetric and not consistent?

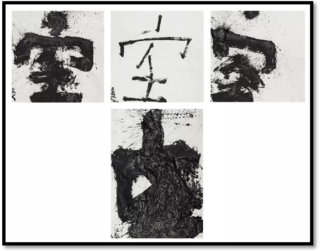

I will look closely at the aesthetic construction of two of his works that were displayed in his solo-exhibition of April 2018 “ Spring and Autumn Calligraphy: the lion roars ( Chunqiu bifa shizi hou春 秋 笔 法 ·狮 子 吼).[1] The centerpiece of the show is a series comprising of four large three by three meter works, that all feature one single, and hardly discernable, character “空”, meaning empty, space, or free time. The word “ empty” is filling up the rice paper surface. The works are written with a very large brush – as big as a mop. It is immediately evident from the works themselves that they are made with speed. The edges are very rough, splashes of ink around the edges point at rapid movements of the brush, and the expressive lashes of ink connecting the separate strokes are unrefined and hastily made. Except for one, which is made with lighter and narrower brushstrokes, the other three works in the series are heavily laden with ink. It is not clear from the work itself if the ink is applied in layers, or brushed on at once with a very wet brush. The immediacy of the aesthetics, however, suggests the latter. All the characters are square-shaped and do not have the characteristic calligraphic bend to the right. Accompanying these works, a large television features prominently in the exhibition space. Upon entering the space you hear screaming (hence, is suggested, the name of the exhibition: “Lion’s roar”(Peng 2018) ) coming from the video featuring Zeng Xiang making these series. It shows Zeng writing down the characters while sweating, screaming and fervently wielding his human-sized brush using his entire body. By showing the process of creating as well as the work itself, Zeng Xiang creates a logic of double immediacy: while the work in itself is already highly suggestive – as is calligraphy in general – of the full body movements of the artist, this becomes even more acute with the visual and audial presentation of its creation (Bolter and Grusin 2000).

The series are reminiscent of the work of modern Japanese calligrapher Yuichi Inoue (1916-1985), who is known to be influenced by the Abstract expressionists and created highly expressionist one single character works that he would often perform live.(Duan n.d.) Also Huai Su 737–799 and Zhang Xu (8th century) come to mind, the two most renowned cursive calligraphers of the Tang dynasty who are generally referred to as “the crazy Zhang and the drunk Su”, and known for their eccentric and explosive performance of live calligraphy, written while drunk, sometimes using their hair as brush. Zeng Xiang agrees there is a similarity with what he is doing but argues that “ performance” ( biaoyan 表演) does not do justice to what he attempts. As an artist, he conveys in our conversation, being in the moment of creation is a state of being ( zhuangtai状态): “Many people in China too think this is a performance. But in fact, it is not. It is the understanding of everything the artist has learned and practiced (xiulian修炼) being mirrored on rice paper at the most effective moment.” (interview with the author). The artist stresses moreover that the inner feelings that come out at this well-timed moment are paramount. Although the end result might be something anyone else can do, the artist, as an accumulator of artistic and, importantly, Chinese traditional knowledge and practice is the only one who can create this, through his feelings, at this moment in time. Critics also focus much on the way traditional calligraphy is (not) part of the “ ugly calligraphers” work – their harsh condemnations typically revolve around the perceived abandonment of tradition and beauty. That calligraphers still carry a responsibility for transitional culture becomes evident in these critiques, one polemic even calling his work “ a national crime” and “ Zeng Xiang Poison” (Zhenji 2018). Zeng Xiang however, feels quite the opposite: his works are steeped in tradition, and he presents himself as a “ dreamer”, someone who takes traditional scripts and viewpoints and molds them for the needs of the modern world, where exhibition and play are important to its survival. (Lu 2014; Zeng 2014).

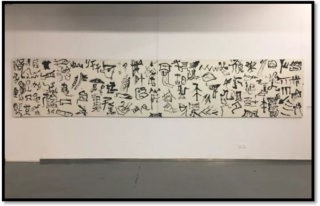

This is apparent in the second large piece called “origin” (qiyuan 起源) in the exhibition, which takes clear reference from the bronze and oracle bone scripts – as the title suggests, the origins of Chinese writing. The artist constructs a bricolage of ancient writings, pictographic characters, actual drawings, lines, dots and hints of animal traces. The ink is crudely brushed on, with flying white interspersed with thick black brushings. Positioned right across from the video in the exhibition space, this work seems to function as an antidote to the fast single character series – while still very expressive, this is a slow work. Its slowness lies, I contend, in the evocations the past. As a viewer, one is invited to discern pictographic character from image, and the legible from the illegible, thus drawing you in with its many possibilities. Moreover, these scripts, although hardly legible, are part of the Chinese script system, since, as Bachner contends, “a master narrative of cultural coherence and scriptural stability incessantly scripts them as recognizably Chinese” (Bachner 2014, 171). What it does, therefore, for the artist to use these scripts in the contemporary, but also for the viewer to recognize them, is an attest that the artist and viewer are both ‘included’ in this binding narrative, and are both aware of their national, cultural and scriptural history. The artist can thus be categorized as not ‘just’ an expressionist contemporary artist, but also a calligrapher.

[1] The exhibition is named after Chinese Buddhist imagery: the lion is a symbol for bravery and strength. Find information on the exhibition here http://exhibit.artron.net/exhibition-56743.html

[1] Interview with author on 28 April 2018, translation by me)

[2] As part of my fieldwork, in trying to grasp how the calligraphy scene operates, I am part of several calligraphy related WeChat groups in which participants chat on calligraphy, share articles, and share their own calligraphic work. In all of these groups, Zeng Xiang’s work was heavily debated at the time of the exhibition. Where some bluntly stated to hate it, other valued his daring works. Similarly, on the Internet, many opinions on his work circulate, as I will show in this article.

[3] Interview with author on 28 April 2018

References

Bachner, Andrea. 2014. Beyond Sinology: Chinese Writing and the Scripts of Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Reprint edition. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Duan, Yi. n.d. “电脑时代新尴尬:提笔忘字•南方日报数字报•南方报网.” Accessed May 3, 2018. http://epaper.southcn.com/nfdaily/html/2011-08/09/content_6997005.htm.

Liu, Zongchao. 2016. “‘丑书’中的‘真’与‘善’ ( The ’ Real’ and the ‘Good’ in ‘Ugly Calligraphy.’” 人民论坛, 2016.

Lu, Mingjun. 2014. “会‘ 玩’ 的 曾翔 ( Zeng Xiang knows how to ‘play’ ).” 中国书画 (Chinese Painting & Calligraphy), 2014.

Peng, Zaisheng. 2018. “书法青年说|感知与困惑:曾翔‘狮子吼.’” 雪花新闻. June 25, 2018.

Wang, Fuming. 2004. “流行书风与丑书 ( Popular calligraphy and ugly calligraphy).” 青少年书法, 2004.

Wei, Wei. 2014. “浅议‘丑书’ ( Talking about ‘ Ugly Calligraphy’).” 现代妇女(下旬), 2014.

Zeng, Xiang. 2014. “我是艺术追梦人 ( I am an art catcher of dreams).” 人物中国书法, 2014.

Zhenji. 2018. “曾翔疯了!再次玷污了中国书法 ( Zeng Xiang Is Crazy! Once Again Polluting Chinese Calligraphy).” 2018. www.sohu.com/a/228871152_482079.